‘The psychoanalyst, like the archaeologist, must uncover layer after layer of the patient’s psyche, before coming to the deepest, most valuable treasures.’

(Freud, to Sergei Pankejeff)

Recently I had the opportunity to visit 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, the serene family home where Freud spent his final year after fleeing Austria. This residence, now preserved as the Freud Museum, offers an extraordinary glimpse into Freud’s interest in collecting archaeological artefacts. I was unprepared for the sheer extent and significance of his collection, and by how clearly his love for antiquities and archaeology influenced the father of psychoanalysis in his radical theories of the unconscious mind.

20 Maresfield Gardens is a beautiful suburban home. While the rest of the home appears typical of a bourgeois family, Freud’s study is a veritable treasure trove of archaeology. The walls are adorned in a ‘pastiche of style,’ (Chernik, 2018) and his cabinets are meticulously arranged by typology, featuring rows of Roman oil lamps, groupings of Greek lekythoi, and shelves of statues from Classical and Egyptian mythology. Despite residing in the Hampstead home for only a brief period, by the time of his death in 1939 the house contained over 2,000 artifacts (Chernik, 2018). These items originated from across the globe, with antiquities from as far as India and China, though his primary interest lay in the ancient Mediterranean, with most of his collection coming from Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, and Etruria. Standing in his study, the impact such a setting makes you want to speak in hushed tones and move quietly. The effect this had on patients ushered into the space must have been intense, however it was Freud himself who spent the most time surrounded by these objects from the ancient world.

I regret missing the exhibition Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire held at the museum the previous year. Kindly, Prof. Daniel Orrells, professor of Classics at King’s College London, provided me with a link to a fantastic podcast series created as part of the exhibition, in which he talks over some of the collection with Prof. Richard Armstrong. These conversations, along with the Freud Museum’s extensive digital collection of his antiques, archives, and online library, provided an excellent starting point for learning more about Freud’s collection (and many larger institutions could learn from the museum’s level of digitalisation!).

Freud’s enthusiasm for the Ancient World

It was not solely collecting antiquities which held Freud’s fascination, his interest in the discipline of archaeology ran deep. He claimed the introduction to Ancient Greek he gained in the gymnasium gave him consolation for the rest of his life (Downing, 1975). Freud closely followed his contemporary Schliemann’s archaeological career and search for the setting for the Homeric Cycle, the ancient city of Troy (excavations now pretty panned by modern archaeologists). In his writings Freud used an ‘archaeological metaphor’ in publications throughout his life, from Studies on Hysteria, first published in 1895, to one of his final works, Constructions in Analysis, published in 1937 (Derose, 2023). Looking at his shelves, Freud’s great respect for the discipline is evident in the many thick tomes concerned with the subject. He even claimed to have read more on the subject of archaeology than on psychology.

Turning to his collection, there is a surprising playfulness to the way Freud treated his antiquities. Freud talked of collecting antiquities as a ‘hobby’, and he was generous with his artefacts, giving intaglio rings to his friends, and slipping Egyptian statues into their briefcases. (Armstrong, 2023). He displayed a childlike enthusiasm for his newest acquisitions, which would join the family for dinner and be treated as dining companions. Despite talking of collecting as a pastime, Freud’s collection held a profound place in his heart, ‘I have sacrificed a great deal for my collection of Greek, Roman and Egyptian antiquities,’ he wrote to the novelist Stefan Zweig, (Winkler, 2023). He started collecting in response to his father’s death in 1896, and in a distinctly Freudian take on the value most often cited as motivation for collectors, Freud stated he believed collectors acquire objects as a substitute for sexual conquests (Martin, 2006). Yet of his own collecting Freud once told Jung, ‘I must always have an object to love’ (Winkler, 2023).

Often dubbed his most treasured antiquity, and the first piece he smuggled out of Austria in 1938 (in a handbag carried by Marie Bonaparte, the great-grandniece of Napoleon) was a bronze statue of Athena.

Bronze Figure of Athena

(Freud Museum London Collection, 2018)

The statuette took pride of place in the centre of his desk and witnesses say he would often hold her. Perhaps he was thinking of her role as the personification of Athens, the birthplace of theatre and therefore a totem of the culture which so inspired his theories. Athena, like so many figures of Greek mythology, is an equivocal figure. It may have been this elusive quality which appealed to Freud when trying to analyse something as slippery and contradictory as the unconscious mind. Interpreting Freud’s intentions is a tall task, as even his own writings often feel like ‘Freud against Freud’ as Wilhelm Reich put it (Downing, 1975). Categorising his oeuvre has always caused issues for academics; Downing asks ‘is Freud therapist or theorist, scientist or poet, realist or romantic? (ibid). Yet I feel the image of the man sitting at his desk, smoking his pipe and holding Athena while letting his mind wander is a striking glimpse into his intentions.

The Role of Antiquities in Psychoanalysis

Freud’s antiquities collecting began with the relatively straightforward process of acquiring artefacts from local shops in Vienna, Salzburg, Florence, and Rome, as well as during his travels abroad. However, once these objects were brought into his study, Freud’s approach diverged significantly from conventional archaeological practices. Rather than preserving these objects for their historical value, Freud used them as visual aids to stimulate his thinking. For him, the act of acquiring antiquities was just the beginning; their true significance lay in the new meanings they inspired. These objects became tools for explaining present-day existence. As Freud developed his psychoanalytical theories, his collection of Classical antiquities served as a visual representation of an ancient past, which he believed was unconsciously embedded in the modern Western psyche. This collection thus became integral to his work, illustrating the profound connections between ancient history and contemporary thought. In Constructions in Analysis, Freud states;

‘Psychical objects are incomparably more complicated than the excavator’s material ones, the main difference between them lies in the fact that for the archaeologist the reconstruction is the aim and end of his endeavors, while for analysis the construction is only a preliminary labor.’

Freud’s collection included more objects from Ancient Egypt that any other culture. Living in the age of Egyptomania, it is unsurprising that Freud collected the kind of ‘wonderful things‘ which obsessed Victorians of all walks of life. Yet Freud’s relationship with such objects went beyond the aesthetic appeal Ancient Egypt evoked for most of society.

Paula Fichtl, Freud’s housekeeper, witnessed Freud patting a marble statue for the baboon-head Thoth each morning and stroking it while writing or deep in thought (Freud Museum, 2018).

Marble statue of Thoth

(Freud Museum London Collection, 2018)

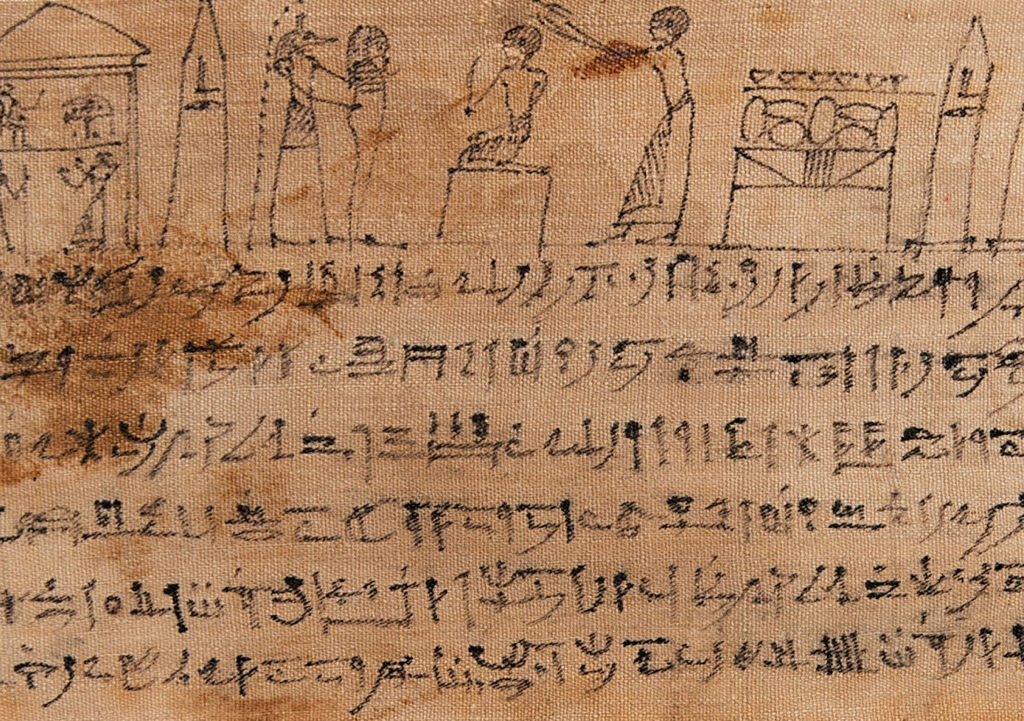

In Ancient Egyptian mythology, it is the baboon-headed Thoth who invented hieroglyphics, and who is the god of intellectual pursuits. In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud recounts the only dream he remembers from his childhood:

‘It is a dozens of years since I myself had a true anxiety-dream. But I remember one from my seventh or eight year, which I submitted to interpretation some thirty years later. It was a very vivid one, and in it I saw my beloved mother, with a peculiarly peaceful, sleeping expression on her features, being carried into the room by two (or three) people with bird’s beaks and laid upon the bed. I awoke in tears and screaming, and interrupted my parent’s sleep. The strangely draped and unnaturally tall figures with birds’ beaks were derived from illustrations to Philippson’s Bible. I fancy they must have been gods with falcons’ heads from an ancient Egyptian funerary relief.’

As well as personal dream visions of hieroglyphs, Freud considered the whole process of interpreting dreams as being analogous to reading hieroglyphs, as ‘he sometimes compared dreams to hieroglyphic texts which could be deciphered with the right tools’ (Chernick, 2018).

Papyrus Fragment (Freud Museum London Collection, 2019)

Freud’s Use of Ancient Mythology

Throughout Freud’s collection there are many mythological figures, and these same myths deeply permeated his writings. The allure of mythology, as James and Hughes (2011) observe, lies in its ‘sheer flexibility and the absence of dogma in their construction’. In antiquity, the original owners of these objects did not distinguish between the religious and the profane. Myths were integral to all aspects of life, from explaining natural phenomena to legitimizing the apotheosis of Roman emperors. According to Prof. Mary Beard, myths are not static; they function as verbs, evolving over time to address contemporary needs (Morales, 2007). This inherent flexibility explains the enduring relevance of myths, as they are continually adapted to fit current contexts. This adaptability underscores why such tales have persisted through centuries, maintaining their significance across different eras. As an aside, as a Classics graduate, I find the contemporary ‘retellings of Greek mythology from a feminist perspective’ which stack up on Waterstones Best-Seller’s tables often inadvertently diminish the incredibly strong roles many women present in the original narratives… I digress. The dynamic nature of myth allows for such reinterpretations, demonstrating its enduring relevance and adaptability.

There are numerous two-faced figures from Classical mythology in Freud’s collection, such as a bronze amulet of Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings, and a bronze container featuring a maenad’s face on one side and a satyr on the other.

Dualism was a central theme in Freud’s thinking, reflected in many of his theories, such as the pleasure versus reality principles, the interplay between libido and aggression, and the life and death instincts known as Eros and Thanatos (Chernick, 2018).

Etching of a bust of two headed Roman god Janus

(New York Public Library Collections, 2024)

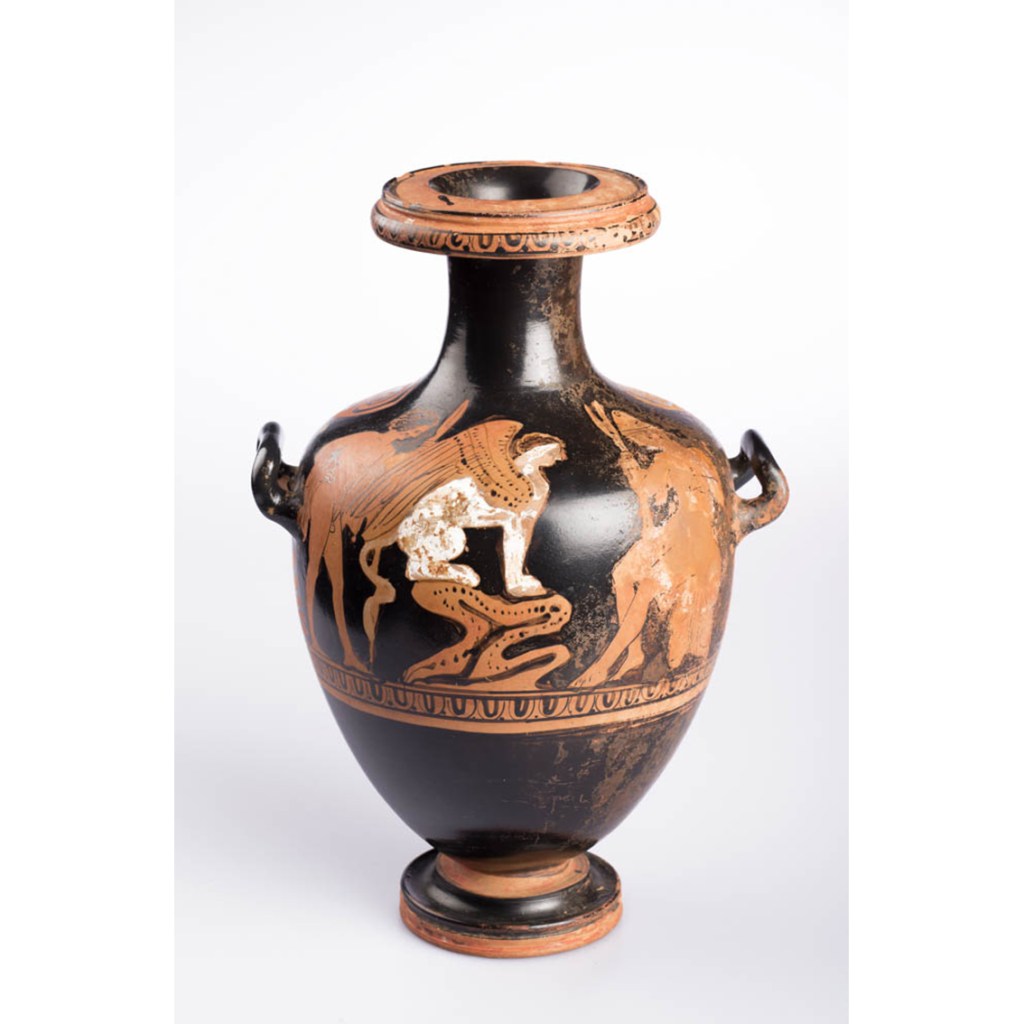

Freud, like so many at the time, considered Ancient Egypt, and his collection of Egyptian antiquities through the kind of mystical, mythical lens which saw Egypt as a feminised, mysterious other (Leonard, 2021). Arguably one of the most mystical of Egyptian creatures, the famous riddle-speaker, the Sphinx, is found all over Freud’s office, with a large etching of the Sphinx at Giza displayed amongst his bookshelves and a terracotta figurine amongst his most prized objects.

Lekythos with Oedipus and Sphinx(Freud Museum London Collection)

(Freud Museum London Collection)

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud aligns himself with a tradition of ‘folk intuition’ akin to ancient practices of dream interpretation (Armstrong, 2023). I would argue that this perspective is also evident in his use of myths. Freud believed that myths harbored essential elements which resonate with the unconscious mind. In his speculative writing, termed ‘metapsychology’ (Downing, 1975), Freud can be seen to myth, as these works require accepting a ‘lets pretend’ attitude of suspension of belief. In 1932, Freud wrote an open letter to Einstein on the topic, stating;

‘It may perhaps seem to you as though our theories are a kind of mythology… But does not every science come in the end to a kind of mythology like this? Cannot the same be said today of your physics?’

Freud’s attitude towards myth as a tool for intellectual inquiry would have been easily understood in the original context of much of his collection; classical Athens. Theatre was born in the context of the explosion of philosophical debate and exploration of logos in contemporary Classical Athens. The first tragedians, Aeschylus and Sophocles, both use myth to explore fate in renowned works such as Prometheus Bound and Antigone respectively.

The Oedipus Complex and Legacy

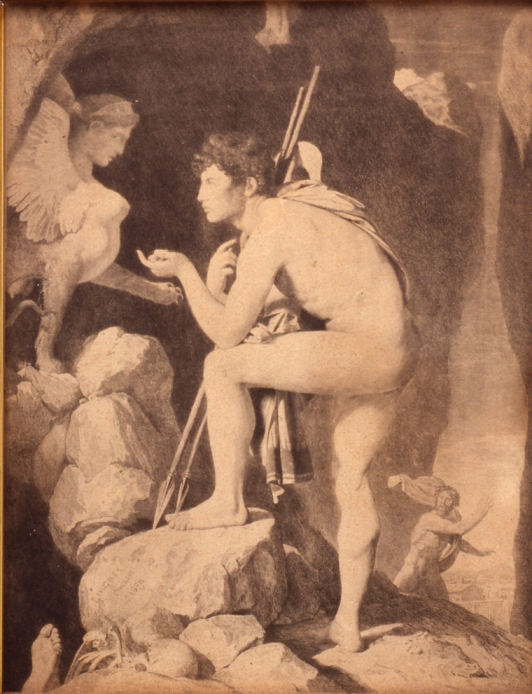

Freud owned a print of French Neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Oedipus and the Sphinx (1808). Of this painting ‘much of the power… derives from the opposition between Oedipus’ classicism and the Sphinx’s orientalism’ (Leonard, 2021), and like Ingres, Freud used myth as a way to examine modern sensibilities.

Freud’s reproduction print of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Oedipus and the Sphinx

(Freud Museum London Collection)

Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex holds a particularly significant influence on Freud’s work. While Freud was certainly not the first to be inspired by this myth, its impact on him was profound. Philosophers have long contemplated Sophocles’ masterpiece; for instance, Hegel interpreted Oedipus solving the answer to the Sphinx’s riddle as ‘man’ as an embodiment of the Delphic maxim Γνῶθι σεαυτόν ‘know thyself’ signifying the birth of human consciousness (Armstrong, 2023). Conversely, Nietzsche critiqued the intellectualization of tragedy, arguing that it should appeal primarily to emotion rather than intellect (Torrance, 2019).

Freud’s interpretation of Oedipus Rex focuses not on the abstract realm of philosophical ideas, but on the play’s narrative. For Freud, the enduring power of the Oedipus myth lies in its illustration of the awakening of psychosexual desires during infancy. He believed this aspect of the play has always resonated with audiences as it touches on unconscious elements of the human psyche when Oedipus unwittingly sleeps with his mother and kills his father. Inspired by this, Freud’s most well-known theory, the Oedipus Complex, posits that during the Phallic stage of development, between the ages of three to six, boys experience unconscious desires for their mothers coupled with castration anxiety, fearing punishment from their fathers. Downing posits ‘Freud’s awe of the sexual is… also awe of man’s imaginative mythmaking capabilities’ (ibid). The study of childhood sexuality is inherently contentious, and the Oedipus Complex is no exception. The theory remains controversial, not only due to its implications, but also in part because its research methodology was based on Freud’s single case study from a child: Little Hans. This case was further unique in that Little Hans’ father, an admirer of Freud, conducted much of the psychoanalysis himself.

Perhaps the most lasting aspect of this theory is the idea that early childhood relationships significantly influence our relationships in later life (Erikson, 1963). Freud’s insights into the deep-seated connections between early experiences and adult behaviour continue to shape our understanding of human development and psychology. Despite the controversies, the Oedipus Complex has become synonymous with Freud and remains one of his most enduring legacies. While drafting this, I conducted a very unofficial survey and asked my friends and family what came to mind when they hear ‘Oedipus’. By a large majority most people responded ‘Complex’ as opposed to the original myth. Evidently, Freud’s impact on the tale of Oedipus has added a new mythic layer to the Greek myth.

Final Thoughts

Freud’s collection of antiquities was immensely significant to him. In a letter to his friend Wilhelm Fliess, Freud expressed that his collection convinced him ‘the Ancient gods still exist’. By using these figures as symbolic of the unconscious mind, Freud played a crucial role in reinvigorating the relevance of these ancient symbols in modern thought. The lasting impact of Freud’s fascination with antiquities and his integration of these symbols into psychoanalysis cannot easily be overstated.

As a final note, all this talk of Greek mythology takes me back to my undergraduate dissertation in Classics, on the role of myth in Classical Antiquity. I went digging through my Gmail for it, and spent a happy hour wincing as I gave it a reread, which in turn led me down a path back to the original comedian, Aristophanes, and to his riotous play The Frogs. There is a truly fantastic performance of it available on YouTube, by Cambridge University 2013 students entirely in Ancient Greek, which I occasionally watch when I need cheering up, and I will leave you with the strongest encouragement to give it a go.

The author in front of the famous psychoanalysis couch at the Freud Museum London, 2024.

Leave a comment