‘Can somebody please tell me if this is real??‘- (Antiquities Collecting Poster)

I am writing a book chapter, and have been spending a lot of time in online forums for collecting small antiquities recently. My tabs bar has been overcrowded with websites with names like ‘Treasure Hunters’ and ‘Ancient Artefact Collectors’. As I mentioned in ‘One Man’s Trash’… The Rising Appeal of Low-End Antiquities I am increasingly interested in why people collect antiquities. Not museum-grade masterpieces which can be traded for enormous sums, that is pretty clear, but the kind of low-end stuff which could be mistaken for rubbish. Rusted Medieval nails, coins so worn they can’t be identified, pottery sherds. The low-end antiquities trade is not about making money. It also doesn’t seem to be directly about prestige; it is about meaning. Collectors find value in the objects themselves, and in the stories they attribute to them and share within collecting communities.

Authenticity, whether real or imagined, is the key ingredient here, the ingredient which transforms junk into heritage. The most common discussions you find in online forums focus on determining whether objects are ‘authentic’. Some forums exist solely to authenticate antiquities, with experienced collectors demonstrating an encyclopedic knowledge of the common forgeries on the market, and passing judgement of ‘real’ or ‘fake’ on hopeful posters finds. These insider experts can identify fakes from the smallest detail, such as specific fabrication methods or artistic styles associated with known counterfeiters. This is in contrast to the more traditional antiquities market, in which outside connoisseurs and dealers verify whether objects are what they are claimed to be. How reliably identifications can be made based on a few photos in a forum thread does not seem to be much questioned.

The Desire for Authenticity in an Uncertain Market

The philosopher Jean Baudrillard famously argued that authenticity is a ‘moral imperative’, a fundamental obsession in postmodern Western thought. The paradox is that while authenticity is considered essential, it remains elusive—especially in the context of heritage. Tourists seek ‘authentic’ cultural experiences, even though many are staged. Walter Benjamin wrote that historical artefacts, in particular, carry an ‘aura’—a unique presence that fosters a connection between past and present. Holding a genuine piece of the past, however rusty and rubbish, links us to the generations before, which can be an intoxicating rush of self-affirmation. We might not be quite as alone as we imagined. The effect authentic fragments of the past can have with this aura is powerful. Online marketplaces, particularly those that cater to the low-end antiquities market, offer endless opportunities to chase this feeling. However, with this thrill comes a fundamental challenge: how can you be sure you’ve bought something genuine?

Even high-end collectors face this problem. The Getty Kouros, a marble statue with debated origins, is displayed with the ambiguous label ‘about 530 B.C. or modern forgery’ (For more on this, I highly encourage you to buy Chasing Aphrodite by my wonderful friend Jason Felch). Similarly, every few years high-profile cases emerge of high end antiquities dealers selling fakes, such as New York’s Sadigh Gallery, which admitted to selling thousands of fraudulent artefacts over three decades. If even prestigious institutions struggle with authenticity, what hope does a casual collector on eBay have?

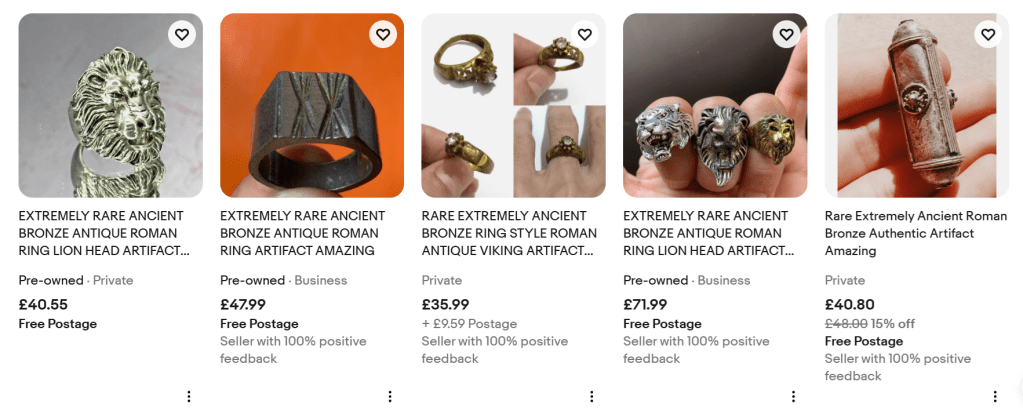

Yet eBay remains a major marketplace for low-end antiquities. Despite the platform’s reputation for fakes, and with only 61% of antiquities listings even mentioning authenticity in the vaguest of terms such as ‘Item is authentic, buy with confidence’, eBay hosts thousands of ‘antiquities’ transactions daily. eBay avoids responsibility for verification, positioning itself as a marketplace rather than an auction house. Some scholars even suggest that a ‘counterfeit feedback loop’ exists, where forgers take inspiration from other fakes, further muddying the waters.

The Psychology of Risk and Reward

So, if authenticity is so uncertain, why do collectors continue buying? Collectors acknowledge the risk of buying duds. On forums, members joke about inevitably buying a forgery at least once. One collector responded to learning that an acquisition was fake with, ‘Maybe in 2000 years it will be valuable!’ I am beginning to think part of the answer lies partly in the psychology of risk. Collecting thrives on a delicate balance: if acquiring items is too easy, interest fades; if it is too difficult, frustration sets in. Research on extreme sports shows that participants are drawn to the thrill, immersion, and personal growth of taking risks—motivations that also appear in antiquities collecting. Uncertainty keeps collectors engaged. Perhaps it isn’t too far of a stretch to compare such collecting habits to gambling, acknowledging the addictive nature of the search. Like online gambling, the low-end antiquities market offers accessible, low-cost ‘bets’ on items, allowing collectors to keep buying despite occasional losses.

Online collecting, then, is not a passive act but an active process of meaning-making. Engaging in collecting, whatever the objects, provides value and a chance to engage with a community of like-minded people. Authenticity, in this sense, is perhaps less about historical truth and more about personal and collective identity. Unlike traditional antiques, which develop cultural biographies through past owners and known histories, many low-end antiquities lack provenance. Instead of diminishing their emotional appeal, this absence allows collectors to construct their own narratives. The only requirement is the belief that an object is genuinely ancient in order to experience the ‘aura’ of living surrounded by remnants of those who walked before us.

Leave a comment